|

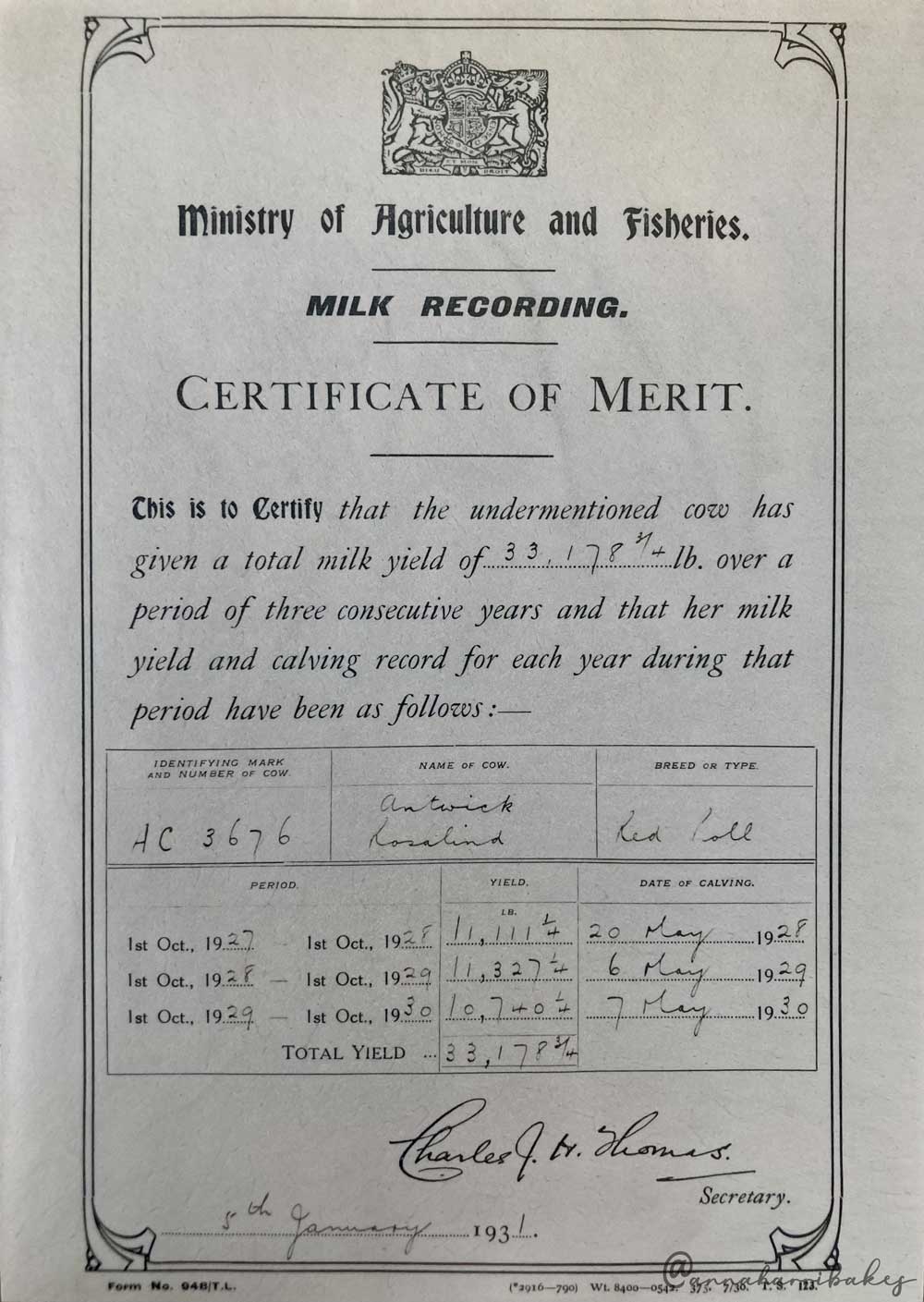

I have a photograph on my wall of my paternal great-grandfather standing proudly alongside his prize cow, a Red Poll named Rosalind. It is accompanied by a ‘Certificate of Merit’ issued by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries. Between 1928 and 1930, Rosalind yielded 33 178 ¼ pounds of milk (about 14,610 litres). My great-grandfather was a cowman, spending his days tending to and milking the cows. Despite his itinerant profession, I’m told that such was his fondness for Rosalind that he would frequently visit her long after he had moved on to a new farm. The 90-year old farmhand Adam Lambsbreath, in Stella Gibbons’ comic novel Cold Comfort Farm, is similarly dedicated to his cows. From the dairy during milking can be heard the ‘spurt and regular ping of milk against metal’, the bucket ‘pressed between [Adam’s] knees’ and his head ‘pressed deep into the flank’ of one of his Jersey cows, Feckless. His ‘gnarled hands’ betray a life spent in the rural outdoors, while their mechanical motions over the cow’s teat reflect a lifetime of milking. Hands would eventually be spared such toil, as machines took over, the one constant being our acceptance of dairy farming as a normal and efficient way of sustaining a population. I grew up drinking free milk from small glass bottles at school breaktime; it was heralded a solution to the nation’s health concerns, nutrient-rich as it is: protein, fat, vitamin B2, B5, B10, B12, iodine, calcium, phosphorus, potassium, melatonin and tryptophan (and sometimes even added vitamin D). I have always looked with pride at that photograph of Rosalind and my great-grandfather, her yield a triumph. Back then, about 13 litres of milk a day was considered prize worthy. Standard intensive milk production today can see cows produce as much as 60 litres per day, which puts cows under great strain and results in a dramatically shortened life span (typically just 5 and a half years). A recent BBC Panorama investigation (‘A Cow’s Life: The True Cost of Milk?’, February 2022), showed the brutal impact on a cow’s body of intensive milking, as well as alleged inhumane conditions in some farms. The exposé revealed shocking undercover footage of cows being kicked, beaten with shovels, and painfully limping due to foot abscesses caused by too much time standing on the concrete floors of milking parlours. Another frequent criticism is environmental: if I want to drink a glass of cows' milk every day of the year, the production of this milk requires 650 square metres of land (more than 10 times as much as the same amount of oat milk). Rearing cows also demands huge amounts of water and emits high levels of greenhouse gases (almost three times the amount of any non-dairy milk, according to a University of Oxford study (Poore and Nemecek, 2018)). Cows belch methane, which traps heat on our planet. Milk was heralded a solution to the nation’s health concerns For these reasons, and due to the growing availability and fashionable nature of non-dairy alternatives, people are increasingly choosing soy, oat, almond, coconut, hemp, and flaxseed milk etc. As of September 2021, two thirds of households now purchase plant-based food and beverages, suggesting that the destiny of Adam Lambsbreath’s beloved cows - Pointless, Feckless and Aimless - might be in their name. Another significant reason for the rise in popularity of non-dairy milk is its purported health benefits. It is an obvious, even necessary option for those with dairy allergies or intolerances. Moreover, dairy milk is sometimes (inconclusively) linked to inflammation in the body, while certain plant milks (such as almond, cashew, macadamia, soy, hemp and flax) contain healthier (unsaturated) fats compared to cows’ milk. On social media, plant milk is usually accompanied by other ostensible indicators of a healthy lifestyle, serving to boost its perception as the healthier alternative. The reality is, of course, a little more complex. Firstly, plant milks often contain a lot more sugar than cows' milk. According to a 2019 Action on Sugar report, if you have standard oat milk in your Starbuck’s Venti Latte, you’ll be consuming two more teaspoons of sugar (and 182 more calories) than if you opted for semi-skimmed cows' milk. Supermarket plant milks also tend to contain a long list of chemical food additives (thickeners, emulsifiers, stabilisers). Even plant milks that have been fortified with factory-produced vitamins and minerals are generally not as nutritious as dairy, according to nutritionist Rhiannon Lambert. Its matrix of nutrients makes cows' milk the superior choice, particularly when we consider the possibility that nutrients added via fortification are not as easily absorbed by the body, according to Professor Sarah Bridle. As well as strengthening our bones, cows' milk may also aid the quality of our sleep and relaxation: it contains the amino acid tryptophan, associated with improved sleep. Milk peptides are also believed to relieve stress, both of which might be why some people enjoy a glass before bedtime. [August 2023 update: according to the largest study of plant-milks to date, in which 233 plant-based milks were tested, only 12% contained the same or higher levels of calcium, vitamin D and protein as cows' milk. On average, plant-based milks had 2g of protein per 240ml, compared to 9g in cows' milk. The University of Minnesota study found that most of the milks fortified with extra nutrients still did not have the same levels as cows' milk, such that the researchers recommend that those drinking plant-based milk consider adding other sources of calcium and vitamin D to their diet. The study did find, however, that many plant-based products are higher in fibre than cows' milk.] Although no plant milk compares nutritionally to dairy milk, soya provides more protein than other plant milks, However, it is also linked to heartbreaking environmental impact. South America soya production destroys the Amazon rainforest, causing deforestation and the displacement of indigenous people. Almonds for almond milk often come from California where intensive farming is the norm: one claim is that it takes 12 litres of water to grow one single almond, and demand is also threatening the Californian bee population. Rice milk, due to the sheer amount of water needed and due to the fact it produces more greenhouse gases than other plant milks, is cited as the least sustainable option. If it’s a choice between dairy milk and soya, almond or rice milk, then, it might actually be best to opt for dairy. Indeed, depending on the type and source of the plant milk, cows' milk from a local dairy, which upholds ethical farming standards, and uses sustainable packaging like bottles or recyclable containers, may be the superior choice. Particularly as farming bodies work to make farming more environmentally friendly: Brades Farm in Lancashire, for instance, which adds Moostral to its cow feed to reduce methane emissions, or research that is assessing whether the microbes in cows’ guts can help to cut down on methane. Some plant milk is linked to heartbreaking environmental impact In August 2022, I visited Berkeley Farm Dairy in Wiltshire, an excellent example of ethical dairy farming. In response to the Panorama outcry, this dairy hosted a series of farm tours to showcase their responsible and organic farming. Established in 1908, the Gosling family care for 180 free-range Guernsey cows, which produce the most beautiful and delicious golden milk. My visit brought to mind that photograph of my great-grandfather and Rosalind: the love and devotion that go into making quality milk, in conditions that shun modern intensive milking, are evidenced in the astonishing contentment and friendliness of the herd. Never have I felt so safe walking through a field of cows! The fact that their cows average about 20 litres of milk a day means that they live far longer than cows milked under intensive programmes: currently their oldest cow is 16 years old. Milked twice a day, they have time to enjoy grazing on the open Wiltshire pasture in summer and on a nutritious organic feed over winter. Berkeley Farm Dairy proves that it is possible to yield quality milk without compromising the health of the cow. Berkeley Farm Dairy proves that it is possible to yield quality milk without compromising the health of the cow Moreover, this farm is environmentally minded and forward-thinking. They recently reintroduced the village milk round, with reusable glass bottles and electric-powered milk floats. As they look to grow more of their own feed, they have even invested in a no-till seed drill to dramatically reduce ploughing, so as to support soil health and reinforce soil’s carbon-capturing ability. Unlike nutritionally empty organic plant milk, organic dairy farming adds value for the customer too: considering the amount of water often contained in plant milk, the purchase price can seem extravagant. The nutrition within organic dairy milk, on the other hand, is not watered down, so it represents greater value for money. However, while supermarkets are rightly confident that we will pay significant sums for a carton of plant milk, they have long been unconvinced that its customers are prepared to pay a fair price for dairy milk. Dairy farmers are repeatedly undercut, which limits the potential for much-needed environmental and ethical innovation. The more we support our local, ethical farmers, the better. Not least because it seems that our taste for cows’ milk has actually been unaffected by the rise in plant milk popularity. Joanna Blythman states, ‘Figures suggest the newer versions [of plant milk] have eaten into the market not for cows’ milk, but rather for soy milk [...] Across the country, sales of cows’ milk are, in fact, increasing’’ (The Telegraph, 13 July 2021). It’s clear that there’s enduring purpose and principle in dairy farming; neither Pointless, Feckless nor Aimless were anywhere to be found at Berkeley Farm. However, if we want to continue to drink cows’ milk, we need to support farmers in making it a credible environmental and ethical alternative to plant milk. And if we are prepared to pay through the roof for plant milk, surely we can afford to spend more on nutrition-dense dairy. The more we support our local, ethical farmers, the better If you enjoy (or require) plant milk, one way of exercising some control over its environmental or health implications is by making your own. I have provided three recipes: oat, hemp and flaxseed. While these recipes won’t compete nutritionally with dairy milk nor with fortified shop-bought plant milks, they make drinking plant milk significantly cheaper and, by checking the production origin of the ingredients and using recyclable bottles, it’s more environmentally friendly too. For ease, I’ve based each recipe on the size of a standard Nutribullet processor, but they are easily doubled. One way of exercising some control is by making your own My tips for choosing shop-bought plant milk:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorHello! I'm Anna and I enjoy researching and writing about food and food history. Archives

March 2023

|