|

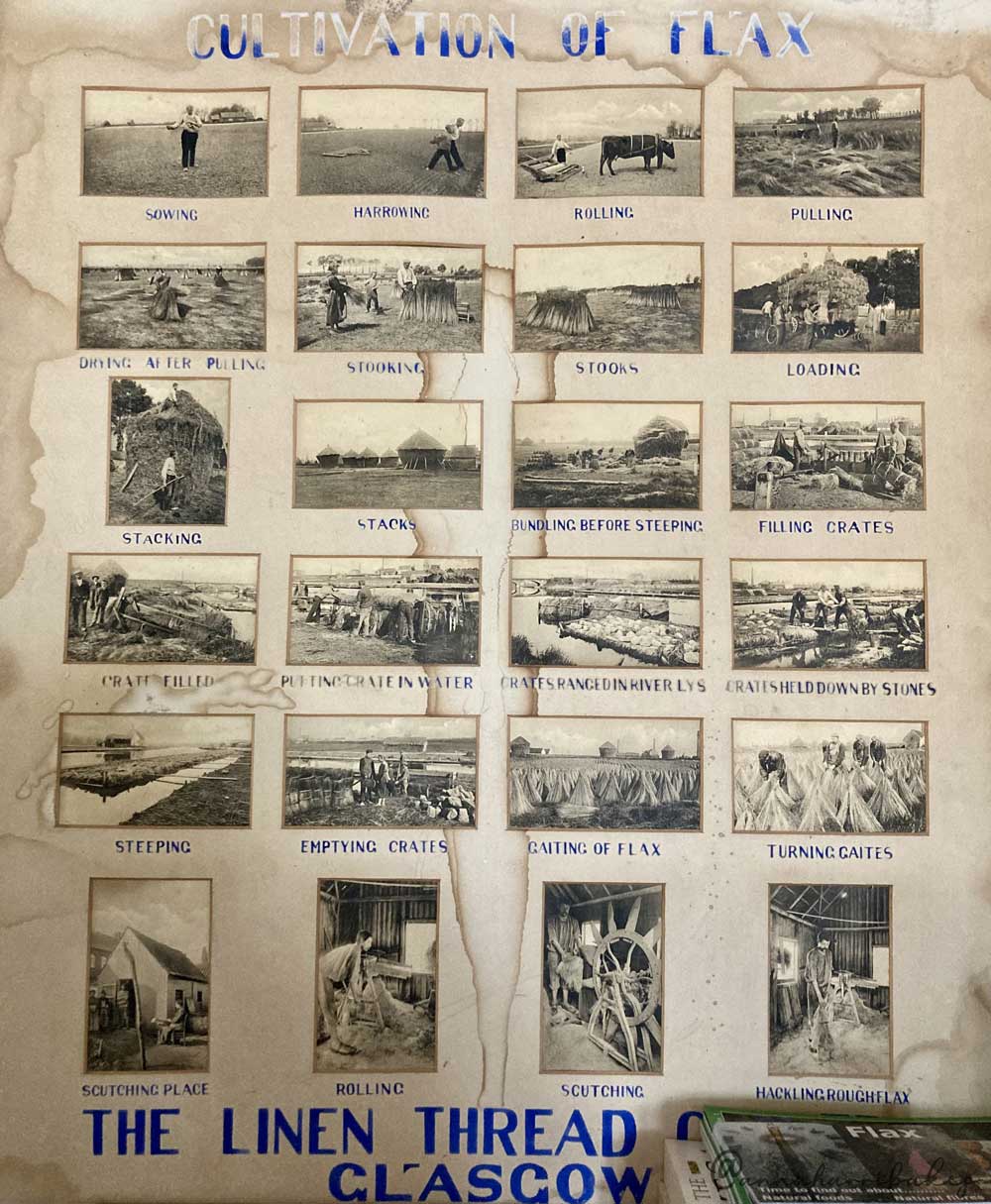

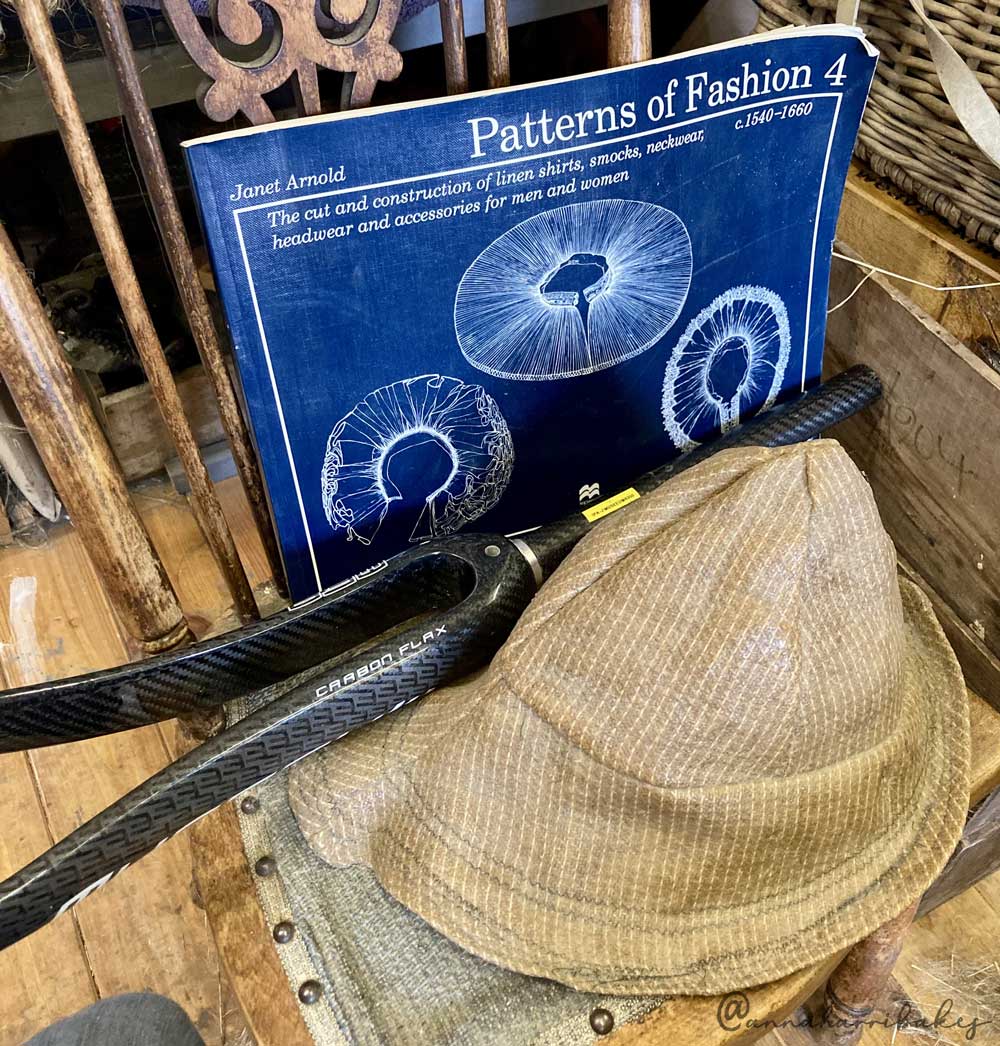

In George Eliot’s novel of the same name, Silas Marner is a linen weaver, one of the ‘wandering men’ who have no clear origin, traversing the land under a burden of flaxen thread, in search of work. Eliot writes during the Industrial Revolution, but sets her story before industrialisation had taken hold. There are shadows of change, however: by the second half of the story, we are informed that ‘the weaving was going down’ and that ‘there was less and less flax spun.’ The historical popularity of flax Flax used to be a very popular crop in Britain. Seeds found at Windmill Hill in Wiltshire show that flax was growing there around 2000BC, though it is believed to have been cultivated as far back as 8000BC in areas such as Syria, Iran and Turkey. Its Latin name, linum usitatissimum, means ‘linen most useful’. Indeed, it is an incredibly versatile crop, from which can be gleaned oil and fibre. Fibre flax is the taller variety, grown for its fibre; linseed is a shorter variety, grown for oil or seed. The Ancient Egyptians finely spun the fibres to make embalming fabric, and used the oil in the embalming process; the Greeks and Romans similarly cultivated flax. Its latin name means 'linen most useful' Once the spinning wheel was introduced in Britain from India in the 1200s, it was possible to spin the fibres for clothing and sailcloth on a wider scale. Stronger than cotton and waterproof, by the Middle Ages it was tightly woven for armour and it was grown as a subsistence crop. During the naval era of Henry VIII, all landowners were obliged to grow some flax. By the 16th century, weaving techniques were being further developed by arriving Huguenots, French Protestants fleeing persecution in France. Apparently members of my own family were Huguenot tailors, so no doubt they were used to weaving linen. As popular as linen was, the industry was a cottage-based one at this stage. As such, it lacked consistency. The advent of the Industrial Revolution in the 1800s meant that techniques such as wet spinning could be used to lengthen and smoothen the fibres. The UK became known around the world as a major producer of fine linens. There was less and less flax spun The forgotten crop However, no sooner had the Industrial Revolution arrived, making spinning easier and more consistent, cotton took over in popularity. Eliot captures this in her novel when the narrator remarks that ‘there was less and less flax spun’. Cotton was cheaper (largely, it must be pointed out, due to slavery) and easier to spin. It is also lighter, and softer, and takes dye better than flax. Moreover, steam ships meant that there was far less need for flax sails, and there was increasing production competition from Russia, France and Belgium. During the two world wars, there was a brief revival of flax in the UK because fabric could not be sourced from Europe. However, by the 1950s - the era of man-made fibres - flax had become a forgotten plant. Growing up in the 1940s and 50s in Northern Ireland, the poet Seamus Heaney remembers the stench of the ‘flax-dam’ that ‘festered in the heart / Of the townland’ (‘Death of a Naturalist’). The dam was the space where the crop was laid out to rot, known as ‘retting’. By the 1980s, flax growing had ceased there too. Flax for the future These days, cottage industry techniques have to be employed if attempting to spin flax in the UK, because there are no mechanised tools left. Simon Cooper at Flaxland in Stroud has made an impressive number of his own machines for processing flax fibre, which I got to try out at one of his superb workshops (see the photographs below). We learnt about the history and entire process of making linen, from growing and harvesting, to retting, rippling, scutching, hackling and spinning. I highly recommend attending one of these workshops to learn more about why the future should be flax. Simon is evangelical about the modern uses for flax, which make it the most exciting crop of the future:

Flax in baking

Flaxseed has been used in baking as far back as 1000BC. We know how nutritionally valuable it is, so it makes sense to incorporate it into our diet more. Here are some ideas for doing so:

Tips for consuming flax:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorHello! I'm Anna and I enjoy researching and writing about food and food history. Archives

March 2023

|