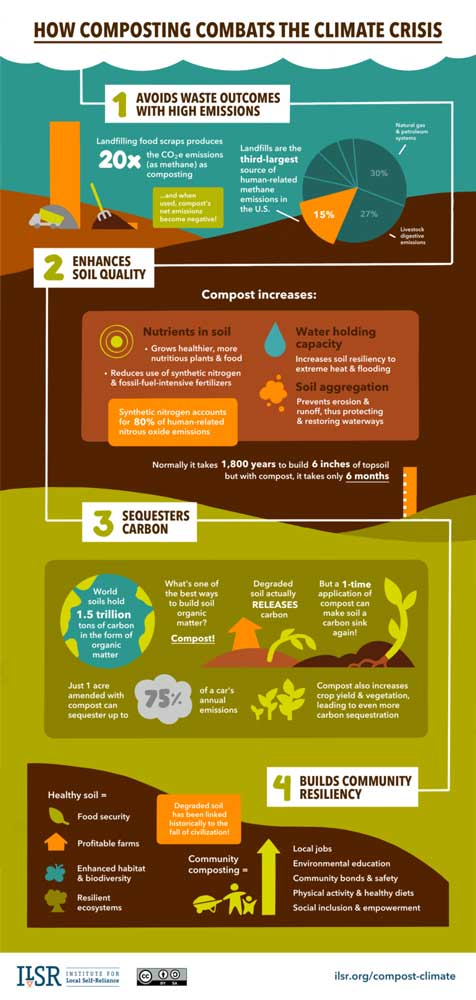

composting to tackle household food wasteIn Emily Brontë’s poem ‘Hope’, hope is a timid bird. Even though it sees the speaker suffering, she does nothing to help. She is frozen by fear. This fear does not excuse her behaviour: Brontë makes it clear that her inaction is cruel and her ‘whispered’ support is ‘false’. In the end, she abandons the speaker entirely, stretching her wings and soaring to heaven: Hope escapes to her own tranquillity, leaving the speaker in ‘frenzied pain’. Hope is also imagined as a bird in Emily Dickinson’s poem ‘Hope is the thing with feathers’. While the bird in Brontë’s poem sits just outside the speaker’s prison of suffering, Dickinson’s bird perches inside the speaker’s soul. Both birds sing but Brontë’s stops as soon as the speaker starts to listen, whereas Dickinson’s ‘never stops – at all’. Dickinson’s bird doesn’t leave the speaker in distress like Brontë’s: in fact, her support intensifies during suffering. Brontë’s is selfish, escaping to her own peace, while Dickinson’s is selfless, giving all and never asking ‘a crumb’ of the speaker. I like the way both poets animate Hope: in externalising it, Brontë and Dickinson draw attention to hope’s potential power over us. It can sustain us or leave us stricken. Sometimes we may feel that hope has a perch inside ourselves – protecting and protective – and sometimes it might feel distant, like Brontë’s bird soaring away. I’ve been thinking about those two poems, with their opposing forces of hope, a lot. This year, it was my resolution to save as much compostable waste from the bin – at work and home – so that its nutrients and energy could empower the next generation of growth. I put small kitchen compost caddies next to the bins, with clear instructions about what should go in each and with reassurance that I would empty them myself each week, and would ensure that the waste is eventually made into compost. After an initial positive response from colleagues at work, and despite the bins’ close proximity, I saw that getting people on board was not going to be easy: I regularly spotted banana skins and compostable teabags in the bin rather than in the caddy. My close inspections of the bin had also exposed the amount of recyclable material that people threw away. Even after my reminders (which were tolerated with humour), and even after moving the recycling bin even closer to the main bin, most recyclable and compostable material ended up in the main bin rather than in the containers where they had at least a chance of a new lease of life. I have made it as easy as possible to compost and recycle, and yet people still don’t do it. Forgetfulness in the midst of a busy day, lack of time, perhaps even laziness or thoughtlessness may all be factors. That banana skin staring up at me from the bin reminded me of the farcical elements of the film ‘Don’t Look Up’: there’s an asteroid coming to hit us, but it’s easier to ignore it. But, unlike ‘Don’t Look Up’, I don’t interpret this inaction as selfish indifference. Maybe it’s something else, implied by the title but not wholly explored in the film: fear-induced blindness. Otherwise called hopelessness. Perhaps I’m overstating it. It’s only composting – why should I expect others to take it seriously? Even a scientist, during lunch one day, dismissed my compost caddy initiative: too small, too insignificant to be worth the effort. As I gather up the small parcel of compost each week and carry it thirty minutes home to my small compost bin, it can be tempting to feel the same. Except that a defiant dam springs up in my mind each time those thoughts ebb in. This is the product of practised hopefulness, a deliberate action consciously and continuously exerted. My response to the scientist was: alone, my efforts are negligible, but perhaps one act can inspire another, and so on, which could gain impactful momentum. Composting could significantly reduce greenhouse gases. Project Drawdown, which considers potential solutions to climate change, reckons that if worldwide composting rose, we could reduce carbon emissions by 2.1 billion tonnes by 2050. The greenhouse gases emitted from composting are a fraction of the gases emitted by food waste in landfill (one study puts it at 14%). No wonder it’s already illegal in Denmark to send organic matter to landfill. If food waste was a country, it would be the third largest emitter of greenhouse gases after the United States and China. And, the problem begins at home: while a lot of food is wasted before it even reaches the consumer, it is estimated that households are responsible for 53% of all food waste in Europe. As depressing as these statistics are, they are also empowering: all too often it’s easy to say ‘what difference can I make? It’s the big corporations that need to change.’ They do, but these figures suggest that the action that individuals take towards food waste could make a tangible difference. There are lots of ways to reduce the damage of food waste to our planet, and a diet consisting of less meat and dairy is one of the most potent. Where it comes to other organic matter, the first step is, of course, trying to avoid it becoming waste in the first place: sensible purchases, creative cooking, strategic use of the freezer are all tactics. The waste that is left – vegetable peelings, fruit skins/pips, eggshells – can be composted. This will reduce the methane that is released into the atmosphere from rotting food in landfill. And the soil that this compost creates will act as a carbon capture, which also reduces growers' reliance on synthetic nitrogen and fossil-fuel fertilizers by creating better quality soil and supporting better crop growth (leading to even more carbon sequestration). It also makes the soil more resistant to flooding and heat, and can enhance the biodiversity of its habitat. Composting builds community bonds and resilience Compost increases the resilience of its immediate soil environment, and can do the same for the human community too. Initiatives like ShareWaste enable people to share food scraps and compost, connecting likeminded individuals to help everyone – regardless of garden space – feel empowered to make a difference. In turn, it promotes social bonds, social inclusion, and healthier living. Imagine the impact of wide-scale composting, on education, on diet, on self-empowerment. Composting is a hopeful effort towards tangible change. My efforts might seem naïve to some. The little pile of slowly degrading organic matter that sits on my shared balcony might seem insignificant, ridiculous even. But, a bit like the robin in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s story The Secret Garden, which hops about in the ‘rich black garden soil’, this pile keeps my hope ‘busily employed’. It is, after all, the robin that brings lonely gardener Ben Weatherstaff and lonely Mary together, and who reveals the secret garden to them. Perhaps Brontë just needed to ask of timid hope, as Mary does of the robin, ‘Would you make friends with me?’ Composting tips

1. Buy a small compost caddy for the kitchen, lined with a compostable bag. Place it in a visible area, labelled with the food that should and shouldn’t go into a compost:

3. Extract coffee from pods using a device such as the Dualit capsule recycler (compost the coffee and recycle the pods) or opt for recyclable coffee pods such as from Grind London. 4. Empty the compost caddy regularly, and clean it carefully to avoid unpleasant smells. 5. Choose a compost bin that is best for your space: if you don’t have space for a conventional bin, opt for a smaller one such as the one I use on a London balcony, Agriframe's RollMix Composter. There are even indoor options if you don't have any outside space. The ZeroWaste website has a great run-down of the different types. 6. Toss the compost regularly – it needs oxygen and heat. Monitor it: make sure air can get through (use torn cardboard or toilet rolls to create some spaces within the compost). If it’s looking a bit wet, add more ‘browns’; too dry, add more ‘greens’. 7. To use the soil, plant seedlings, fold it into a vegetable patch, or donate it to a gardener or to a community compost (e.g. ShareWaste) if you don’t have your own outdoor space. How to reduce the carbon footprint of food

0 Comments

|

AuthorHello! I'm Anna and I enjoy researching and writing about food and food history. Archives

March 2023

|